As flexibilities introduced as part of the COVID-10 public health emergency recede, coverage gains in Medicaid made during that time could be lost as well, according to a new report by the Urban Institute.

Emergency measures such as the Families First Coronavirus Response Act helped swell Medicaid rolls by 22 million people since February 2020. In addition, higher premium subsidies on the Affordable Care Act's (ACA's) exchanges also drove down the number of people without insurance, the analysts said.

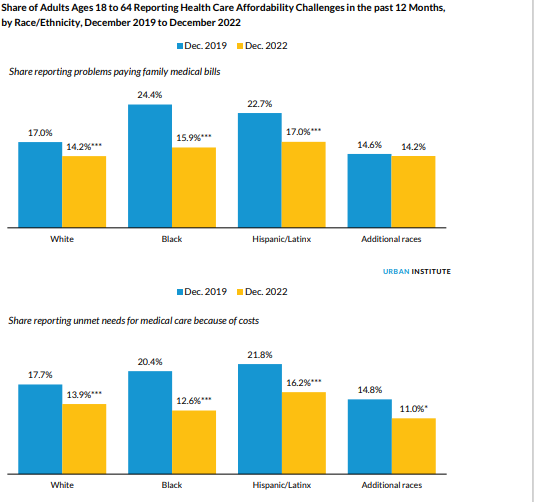

Researchers looked at data between December 2019, or just before the pandemic began, and December 2022, the latest data available in the Urban Institute’s Well-Being and Basic Needs Survey (WBNS). The study was backed by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

They examined two obstacles to getting healthcare: problems paying medical bills and choosing to put off needed care because of the expense. The share of adults who said they had problems paying the bills in the last 12 months shrank from 18.7% to 15%, according to the report.

In addition, the share of adults who said they had to put off medical care because it cost too much in the last 12 months declined from 18.5% to 13.9%.

State Medicaid programs were given the go-ahead to restart eligibility determinations in April, and the findings in the Urban Institute’s report echo those in a KFF report issued last week digging into early disenrollment data. That study found many disenrollments occurred because of procedural reasons, which led KFF researchers to conclude that many people who are losing Medicaid coverage might still be eligible.

The Urban Institute report found that some states are looking to avoid seeing too many people losing coverage by granting waivers to provide Medicaid coverage from birth to age 5, helping with the transition from Medicaid to the ACA marketplace and providing coverage to immigrants.

All demographic groups benefited from the increased access to coverage, according to the report, but especially Black and Hispanic patients. The number of Black adults who said that they had trouble paying medical bills declined from 24.4% to 15.9%. In addition, the number of Black adults reporting unmet healthcare needs because of costs fell from 20.4% to 12.6%.

Researchers noted that Hispanic adults have among the highest uninsured rates, but they too benefited from the expanded coverage, with far fewer reporting having problems paying medical bills during this period (22.7% to 17%) and unmet needs for care (21.8% to 16.2%).

The ability of families to pay medical bills during the timespan differed greatly depending on income as a percentage of the federal poverty level. While the percentage of adults with incomes below 100% FPL didn’t change, the number of those in this group who said they delayed care because of cost dropped from 27.2% to 18.8%.

The report stated that “adults with incomes just above that level—between 100% and 200% of FPL—experienced some of the largest reductions in both measures: the share with problems paying medical bills fell from 32.4% to 24.9% and the share with unmet needs for care fell from 31.9% to 24.1%.”

A decrease in both types of affordability challenges occurred for adults with incomes between 200% and 400% of FPL, but the change was not statistically significant. Adults with the highest incomes of 400% of FPL or more reported a decline in problems paying medical bills (10.1% to 6.1%) as well as a decline in putting off needed care (9.3% to 6.3%).

“Given the relatively small sample sizes of racial and ethnic subgroups in the WBNS, it will be important to use federal survey data to further examine changes in racial and ethnic disparities in the ability to pay for care,” the report stated.